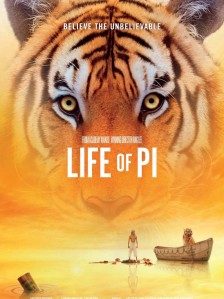

Recently I lead a retreat on the question “What is Truth?” Echoing Pilate’s perennial question to an accused Jesus, we began by exploring the layers of truth in the award-winning, and made into a movie, novel Life of Pi by Yann Martel.

Religious belief is one of the most fascinating themes in Life of Pi. Throughout the novel, Pi’s beliefs mature. His introduction to religion comes through befriending his mentors who are a Catholic priest, a Jewish Rabbi and a Muslim Imam. He willingly joins each religion through their various initiation rituals and catechetical instructions. Pi is equally comfortable praying in a church, a mosque or a synagogue. One of the most amusing scenes in the story is the chance encounter on the street between Pi and his three mentors, each “claiming” Pi as their own. However, only when he is on his forced journey at sea, does Pi realize that he truly believes in God. His faith is tested in a way that it was not tested earlier in his life.

Religious belief is one of the most fascinating themes in Life of Pi. Throughout the novel, Pi’s beliefs mature. His introduction to religion comes through befriending his mentors who are a Catholic priest, a Jewish Rabbi and a Muslim Imam. He willingly joins each religion through their various initiation rituals and catechetical instructions. Pi is equally comfortable praying in a church, a mosque or a synagogue. One of the most amusing scenes in the story is the chance encounter on the street between Pi and his three mentors, each “claiming” Pi as their own. However, only when he is on his forced journey at sea, does Pi realize that he truly believes in God. His faith is tested in a way that it was not tested earlier in his life.

Earlier in the novel, Pi notes that religion puts many people off today because they believe it constrains their freedom. He criticizes such people for not realizing that ‘freedom’ outside of safety and comfort, status and order can be incredibly frightening. Pi learns that the stakes at sea are much higher, when there is less order and no comforts of any kind; every day he faces life or death situations. It is his religious faith that gets him through, which is an implicit rebuke to those who believe faith limits freedom.

It is often said that faith grows our best and most enduring qualities in times of trial and hardship. Pi seems to experience exactly that on the open seas; many will resonate with this insight. Faith can deepen in times of suffering. It doesn’t justify the suffering, however — never. And the potential to grow through suffering is only that — a potential. God honours our human freedom like none other. We have to choose the growing. There is good reason why Jesus asked regularly, ‘do you want to be well?’ I am reminded of an especially painful experience when a close friend gently said: “I’m not denying your pain — it is real, it is justified and deserves to be honoured. Take all the time you need to grieve. Just remember that God is eagerly waiting to teach you many things through this hardship.” And so, when I was ready to slow down my weeping and wailing, I asked God to teach me — I willed it. And God did, in ways that far surpassed my expectations and hopes.

Pi’s insights into freedom and his faith development really got me thinking about today’s so-called “secular” culture and Christian faith, including my own. His discovery of false and true freedom helped me understand why our western culture seems so much less inclined to embrace a religious faith, whether traditional or even contemporary. So many of us live comfortable lives cushioned by material goods and job security (although that’s eroding more and more), by a long-established social order and a taken-for-granted freedom of expression. Who needs religion?

While not necessarily so, such a question could arise from an adolescent-type arrogance. Our so-called post-modern culture not only questions the need for traditional religion, but looks bolstered by a sense of freedom that seems more centered on self than on others and the common good. Interestingly, Pope Francis’ instructions for this year’s Lenten season echo a similar concern: ““Usually when we are healthy and comfortable, we forget about others; we are unconcerned with their problems, their suffering, and the injustices they endure. Our heart grows cold.” Before we dismiss the need and value of religion, humility and caution would be well-advised lest we risk falling into an outright denial of our origin and daily sustenance of life: if God would ever stop loving us we would cease to exist.

My own parents embraced this idea that religion was obsolete, but for slightly different reasons. Having grown up themselves in a rather restrictive form of Catholicism as well as in poverty and hardship, they wanted nothing more than to “free” themselves from both these yokes — understandably so. As a result, both of them opted for a non-religious funeral. When I began to immerse myself more deeply into a traditional Catholicism, all they could see was a going “backwards” (their word, not mine) into a thing of the past. Sad, really, as their example of love, service and sacrifice laid strong spiritual foundations for me, but they could not see that.

Have our spiritual needs really changed that much from our ancestors? Is our freedom to “do what we want when we want and with whom we want” an authentic freedom? Or are we suffering a massive dose of collective delusion, lulled asleep by affluence, blissfully sinking into amnesia about the fact that our deepest needs and hungers remain spiritual in nature? Who is really free — those who have everything but still feel empty, or those who have nothing yet burst with joy, generosity and hospitality and those who can sing even as they meet death? Just asking.

A lot of horrific things continue to happen in the world in the name of religion. No rationalization can ever justify that. However, sometimes true inner freedom is on full global display as a fruit of religion. That is what I saw and heard when the 21 Egyptian Coptic Christians were beheaded in Libya last month. Martyred for their faith in Jesus, their witness was immediately elevated to sainthood (incidentally, more Christians have been killed for their faith in the past century than in all previous centuries combined).

The icon above, currently circulating in cyberspace, was written within weeks of their brutal murder by the artist Tony Rezk (Read the artist’s own blog entry here and an interview with him here). It depicts the new martyrs receiving the crown of glory in heaven. Some will consider this image incomprehensible and even outrageous; others see in these 21 Christians a powerful illustration of authentic freedom. I have not watched the beheading-video, and I will not, but I have heard that the sound on the video was praying: “Ya yesua irhammi — Jesus, have mercy on me.”

No matter our feelings about religion, we can honour these 21 new martyrs by showing a personal interest in their stories, by letting our hearts be moved by the unspeakable sorrow of their families. And while we’re at it, may their brutal, innocent death bear fruit in our stopping to reflect: in what or whom is my sense of freedom and faith grounded? Is my freedom a freedom from or a freedom for, born of God and serving my neighbour in need? Is my own faith strong enough to hold me steady in the trials and storms of life, encouraging me to choose life and growth in the midst of the painful seasons of my existence? What or who am I willing, freely, to die for?

“If you stumble over believability, what are you living for? Love is hard to believe, ask any lover. Life is hard to believe, ask any scientist. God is hard to believe, ask any believer. What is your problem with hard to believe?” (Life of Pi, Yann Martel, 2001)

“Life is so beautiful that death has fallen in love with it, a jealous, possessive love that grabs at what it can. But life leaps over oblivion lightly, losing only a thing or two of no importance, and gloom is but the passing shadow of a cloud…” (Life of Pi, Yann Martel, 2001)

For a Lenten reflection related to the above content, read Margery Eagan’s column here.

Thank you for reading this reflection. For private comments, use the Contact Form below; for public comments use the space below “Leave a Reply.”

http://www.prairie-encounters.ca